Frogs Use Their Eyes To Swallow Food

A common adage around the world is “eating with your eyes.” You’ve probably heard this before; I know I have. It means appetizing food is likely to be eaten. This adage takes on a whole new meaning for frogs…

Frogs actually do eat with their eyes. More accurately, frogs use their eyes to help them swallow food. This article will shed some light on how this is possible and why it happens.

Researchers Study The Eye Retraction of a Northern Leopard Frog

For years, researchers suspected the reason frogs retract their eyes while eating was to help them swallow their food. Testing the theory with specialized equipment had not taken place yet.

For, strange as it may seem, the large eyes of the toad can be pressed down into the mouth as far below its roof as they rise above the head, and the movement aids effectually in swallowing.

Mary C. Dickerson, American herpetologist

The quote above[1] comes from Mary Dickerson’s 1906 publication of The Frog Book (link goes to Amazon). Mary Dickerson, an American herpetologist, made keen observations and accurately concluded the eyes play a critical role in the swallowing process for Anurans (frogs and toads).

In 2004, with the use of special equipment, researchers were able to definitely conclude that at least one frog, the Northern Leopard Frog, retracts its eyes to aid in swallowing moderately-sized insects. Dickerson was right.

Robert Levine and a team of researchers at the University of Massachusetts used behavioral observations, electromyography, cineradiography, and nerve transection experiments to test the contribution of eye retraction using a Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens)[2].

So, it’s safe to assume that if one species of frog uses its eyes to help them swallow food, other frogs and toads do the same thing. Perhaps not all of them, but some of them.

One only needs to observe a frog feeding to see its eyes in action.

How and Why Frogs Use Their Eyes to Swallow

To better understand the process, it is fitting for me to explain both why and how frogs use their eyes for swallowing.

- How it works – The muscles associated with the frog’s eyes retract their eyes into their oropharynx. By doing so, the eyes help to push the food towards the esophagus.

- Why they do it – The saliva on a frog’s tongue is very sticky. Retracting their eyes helps knock the food off its tongue.

A frog’s eyes are an accessory swallowing mechanism. It’s not the primary means of swallowing – that function belongs to the tongue.

Frogs have incredibly soft tongues with sticky saliva. The soft tongue envelops the frog’s prey on contact, rather than pushing it away. The sticky saliva, of course, adheres the prey to their tongue. This enables the tongue to spring back into the frog’s mouth, bringing the prey with it.

Related: What Do Frogs Eat?

Once in the mouth, retraction of the eyes helps move the prey into the esophagus and knock the food off the frog’s tongue.

Also, some frogs have teeth but they’re not used for chewing. They’re simply used for holding on to their prey before swallowing.

More About The Eyes of Frogs

Anuran eyes vary in construct. Some have small eyes while others have large eyes. One of the most notable features of tree frogs, for example, is the size of their eyes in proportion to their head and body. Not all frogs are like this, as you’ll soon learn.

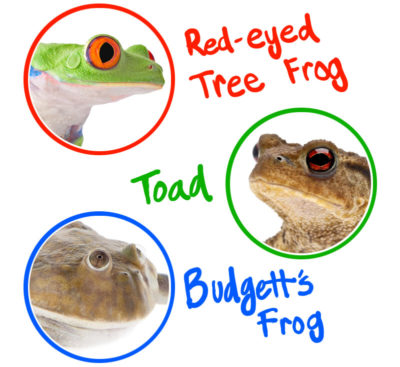

When comparing the eyes of a Red-Eyed Tree Frog, a toad, and a Budgett’s Frog, one can see differences. See the picture below.

When comparing the eyes of a Red-Eyed Tree Frog, a toad, and a Budgett’s Frog, one can see differences. See the picture below.

Upon closer inspection, you can see a Red-Eyed Tree Frog has large eyes in proportion to its head. The eyes are on either side and clearly protrude above the head.

The toad has eyes on either side of its head too, but they’re slightly smaller in proportion to the size of its head. The eyes don’t extend above the head as much and their brow area is more pronounced. Most “true toads”, those in the Bufonidae family, have more protection around their eyes.

Perhaps the biggest differences can be seen with Budgett’s Frog. Both eyes rest atop its head and they seemingly point upward.

Most frogs have a 180-degree field of view, as their eyes are atop their head. Their vision overlaps only slightly in some; none in others.

Also, some amphibians appear to be colorblind[3]. More studies are needed on this topic. Some findings suggest the Rana and Bufo Genus can distinguish between red and blue, with the former, and blue and violet with the latter.

A new study, however, suggests that frogs are capable of seeing color in low-light situations[4]. In the case of humans, we might only see black and white in a forest at night with minimal light from the moon. Frogs might actually be able to see color in this situation because the rods in their eyes could allow them to see colors in extreme dark.

TLDR; A Short Summary

Frogs and toads have unusual eyes with varying constructs. Observing them eating flies and various insects is entertaining, too! Their sticky tongue flies out of their mouth in the blink of an eye. Upon retrieving their meal, one can almost always observe a frog closing its eyes while eating.

That is because frogs use their eyes to help them swallow their food. The eye muscles retract their eyes into a part of the mouth. Doing this pushes their meal off their tongue and into their esophagus.

References

- Dickerson, Mary. “The Frog Book.” The American Toad, Dover Publications, 1969, pp. 81–82.[↩]

- Levine, Robert P., et al. “Contribution of Eye Retraction to Swallowing Performance in the Northern Leopard Frog, Rana Pipiens.” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 207, no. 8, 2004, pp. 1361–68. Crossref, doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00885.[↩]

- Hofrichter, Robert. The Encyclopedia of Amphibians. Gardners Books, 2000., p. 89[↩]

- Kelber, Almut, et al. “Thresholds and Noise Limitations of Colour Vision in Dim Light.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 372, no. 1717, 2017, p. 20160065. Crossref, doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0065.[↩]