Poisonous Frogs: A Complete Guide

Brightly colored frogs and toads are some of the most beautiful creatures on earth, but did you know some are poisonous? It’s true…

Most anurans (frogs and toads) have toxins on their skin. Some are more dangerous than others but most frogs are harmless to humans under normal conditions.

First, let’s cover the basics: A toxin is a harmful substance. Poison is typically swallowed, inhaled, or absorbed. Venom is typically injected via fangs or stingers.

With this in mind, most frogs are considered poisonous because they don’t inject toxins via fangs or stingers. Out of 7,000+ species, only two species are considered venomous.

Encounters with amphibians are rarely dangerous. Severe damage and death are rare but possible. There are documented fatalities as a result of poisoning from frogs. Most of them involve licking, swallowing, or eating frogs, toads, tadpoles, or eggs.

Table of Contents

The Reason Frogs Are Poisonous (And Slimy)

Frogs are small and have limited defenses. They’re near the bottom of the food chain. Moreover, they don’t have scales or fur to protect themselves from the sun or microorganisms found in the water they live in.

Because of this, frogs secrete mucous and toxins for protection.

- Protection from microorganisms: Frogs spend much of their lives in wet, moldy environments, teeming with harmful bacteria. The frog’s mucous layer has an antibiotic function that helps prevent infection.

- Defense against predators: If a predator attacks a frog, the toxin will leave a bad taste in the predator’s mouth. Some toxins cause foaming in the mouth, severe irritation, paralysis, and even death.

Simply put, frogs secrete mucous and toxins on their skin. The mucous layer protects them from the sun and microorganisms while the toxins help defend against predators [1].

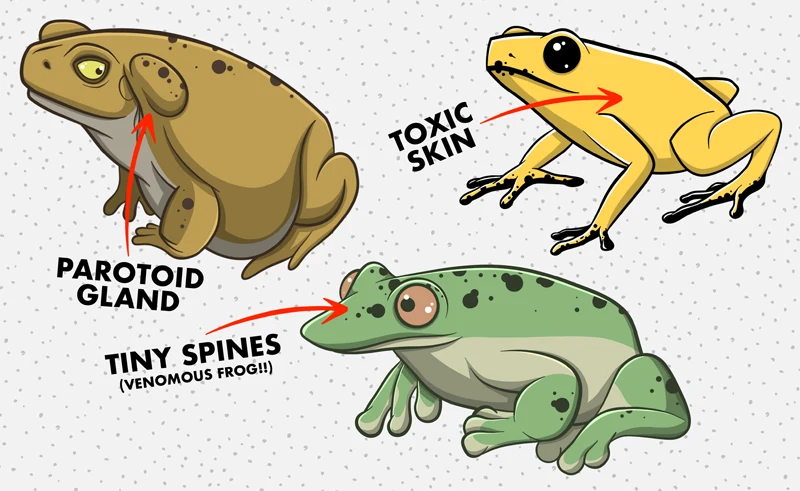

Toxin Locations on Frogs & Toads

Now that you know why frogs are poisonous, let’s take a look at where the toxins are located. Most frogs have poison glands covering their entire body. Toads are slightly different, having a large gland behind their eyes. Finally, frogspawn can be toxic as well.

The following sections cover each in more detail.

The Skin

A frog’s skin is protected by toxins. Granular glands cover their whole body, including the legs. So, most frogs are protected no matter where a predator grabs them.

There may be higher concentrations at different locations on the body.

Also, the potency of toxins ranges drastically from one species to the next. Most are harmless to humans, while others are potentially fatal. It’s mostly small animals that are affected by frog poison.

Parotoid Gland

The parotoid gland (also spelled: paratoid) is a gland located behind a toad’s eyes. This gland is mostly found on true toads, those in the bufonidae family, and salamanders.

Inside the gland is a milky, alkaloid substance. There are many different toxins but they’re collectively known as bufotoxins.

Bufotoxins are typically squeezed from the gland when a predator bites the toad, squeezing the parotoid gland. However, some species, like the Cane Toad, are capable of spraying the toxins up to 12-inches [2].

Eggs, Embryo, and Tadpoles

Most studies observe poisons in adult frogs, but not many examine their offspring. It may leave you wondering if eggs or tadpoles are poisonous. Luckily, we have the answer thanks to a recent finding.

A study on Strawberry Poison-dart Frogs (Oophaga pumilio) detected alkaloids (toxins) in their eggs and tadpoles [3]. Alkaloids were found in some eggs and tadpoles at different stages.

This isn’t the only evidence that frogspawn is poisonous either. In 2007, a 19-year-old woman was admitted to an emergency room after ingesting toad eggs[4].

The Risk of Frog Poisoning to Humans

Now that you have a greater understanding of why frogs are poisonous and where the toxins are located, I’ll explain the potential dangers for people.

The majority of amphibians are not dangerous to people under normal circumstances. However, certain situations have the potential to be harmful or deadly. Listed below are abnormal circumstances that could be life-threatening.

- Licking or Ingesting frogs, toads, or their offspring. The greatest chance of injury or death comes when frogs are consumed.

- Touching your eyes, mouth, or nose after handling a highly-toxic frog. Rubbing your eyes or touching your mouth after handling a highly-toxic amphibian is dangerous. Also, be mindful of open cuts on your hands.

- Amphibians are known to carry salmonella. Always wash your hands after coming into contact with amphibians.

Frog Toxins

This section covers information regarding frog toxins, their potency, and what they do. There are many different kinds. Instead of trying to list every single one, I’ll just cover four of the most well-known toxins.

- 5-MeO-DMT – A powerful hallucinogen[5] carried by the Colorado River Toad, also known as the Sonoran Desert Toad. It’s potentially lethal to people.

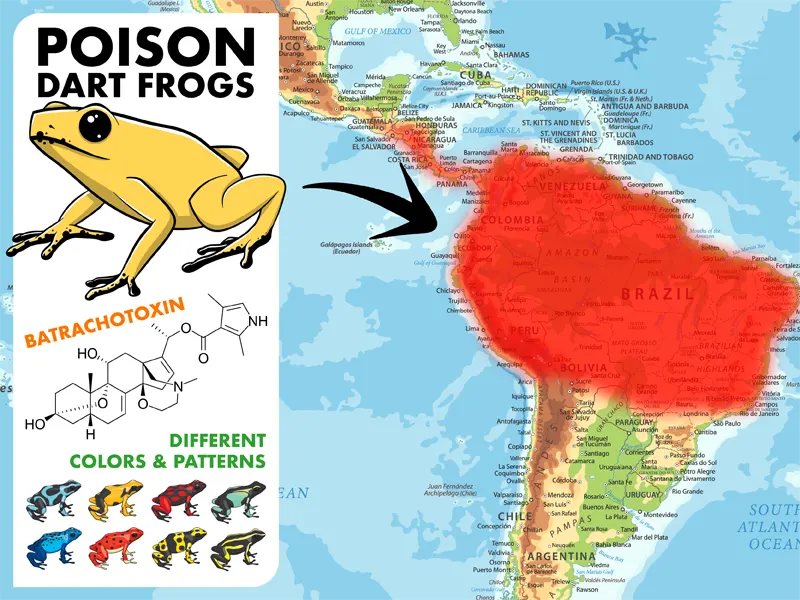

- Batrachotoxin – This is possibly the most famous neurotoxin found in frogs. As little as 0.00001 grams can kill an average-sized adult male[2]. Primarily found in poison-dart frogs.

- Bufotoxin – Mostly found in the parotoid gland of true toads (genus: Bufo). Potency varies between species. Bufotoxin can be fatal to animals and humans. A review of toxic animal poisoning in China revealed 5 cases of bufonis poisoning[6].

- Tetrodotoxin – This toxin is most known due to the popular Japanese food dish made from Fugu. Although uncommon, it has been found in a few species of frogs.

If that list of toxins wasn’t enough to worry you, continue reading…

Salmonella

Both reptiles and amphibians are known carriers of Salmonella. The bacteria is commonly transmitted after coming into contact with their droppings (urine a feces).

According to the Mayo Clinic, Salmonella is a bacteria disease that affects the intestines. The bacteria can live in the intestines of animals and humans, and they’re shed through stool [7].

One study examined frogs from North-East Thailand for the presence of salmonella [8]. The samples contained farm-raised frogs and wild frogs from an urban area and a protected area. According to their study, salmonella was detected in most of their samples.

Related: Are Frogs Poisonous to Dogs?

How to Identify Poisonous Frogs

There are two important things to know when trying to identify really poisonous, dangerous frogs.

- Most of them are located in Central and South America.

- They usually have aposematic coloration (bright, vivid colors).

Most of the concerning species are Poison-dart frogs. These frogs are small, colorful, and typically found in Central and South America.

See the illustration above for a map and pictures of dart frogs. If you’re considering traveling to one of these areas, it may be worth your time to do more research on this topic.

So long as you’re not licking or eating frogs, toads, tadpoles, or frogspawn, you usually don’t need to worry. Definitely avoid touching wild poison dart frogs regardless, and always wash your hands with soap and water after touching any reptile or amphibian.

My List of Potentially Harmful Species

The table below lists all the frogs I believe a person should know about. By the way, most frogs in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom aren’t dangerous to people under normal conditions.

| Image | Name | Potency | Location(s) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cane Toad (Rhinella marina) | Medium | Australia, Central & South America, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Taiwan, United States View on iNaturalist → | Invasive species in many parts of the world. |

| Colorado River Toad (Incilius alvarius) | Medium | Mexico, United States View on iNaturalist → | Some people lick these toads to get high. |

| Poison Dart Frogs (Dendrobatidae) | High | Central America, South America, Hawaii View on iNaturalist → | There are small populations in Hawaii. |

| Bruno’s Casque-headed Frog (Nyctimantis brunoi) | High | South America View on iNaturalist → | Very uncommon species and they’re venomous. |

| Most Frogs & Toads | Low | All continents except Antarctica. |

Related: Are Salamanders Poisonous?

Frequently Asked Questions

This section contains some of the most frequently asked questions regarding frog poison.

A recent study found that poisonous frogs are able to resist their own toxins. An amino acid changes the configuration of a receptor, which decreases its sensitivity to its toxin[9].

Yes, there are venomous frogs. At the time of writing this, there are at least two known venomous frogs. Bruno’s casque-headed frog and Greening’s frog are considered venomous because tiny spines on their skull can be used to inject toxins into their predators.

No, not all colorful frogs are dangerous. One example of a harmless, colorful frog is the Red-Eyed Tree Frog. They are bright red, blue, orange, and green, and they are not highly toxic.

Tribes from Colombia used the potent neurotoxin from select poison-dart frogs for hunting[10]. They would agitate the frogs and collect poison from their skin. After that, they coated darts with the poison (hence their name). They’re also known as Poison-arrow frogs.

Yes, you can die from frog poisoning under the right circumstances. It is rare but there are documented fatalities [11]. Most cases involve people ingesting frogs, toads, eggs, or tadpoles, swallowing them on a dare, or licking toads to get high.

TLDR; All About Frog Poisons

In summary, most frogs are harmless to people under normal circumstances. There are a few species that are deadly and there have been fatalities caused by frog poisonous.

Poison dart frogs are among the most toxic frogs in the world, and they’re mostly located in Central and South America. See the table (with pictures) about the potentially harmful species in the section above.

Most fatalities occur when people swallow a frog or toad, eggs, or tadpoles as food. Amphibians can carry Salmonella, too. If you happen to hold a frog, just be sure to wash your hands afterward. Avoid rubbing your eyes or touching your mouth.

Stay away from poison dart frogs and just know that there are some potentially deadly frogs and toads around the world.

It’s best to admire frogs and toads from a distance anyway. They’re delicate animals with permeable skin.

References

- Saporito, Ralph A., et al. “A Review of Chemical Ecology in Poison Frogs.” Chemoecology, vol. 22, no. 3, 2011, pp. 159–68. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00049-011-0088-0.[↩]

- Hofrichter, Robert. The Encyclopedia of Amphibians. Gardners Books, 2000., pp. 112[↩][↩]

- Stynoski, Jennifer L., et al. “Evidence of Maternal Provisioning of Alkaloid-Based Chemical Defenses in the Strawberry Poison FrogOophaga Pumilio.” Ecology, vol. 95, no. 3, 2014, pp. 587–93. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0927.1.[↩]

- Kuo, Hung-Yi. “Life‐threatening Episode after Ingestion of Toad Eggs: A Case Report with Literature Review.” Emergency Medicine Journal : EMJ, vol. 24, no. 3, 2007, pp. 215–16. BMJ, https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.044602.[↩]

- Araújo, Ana Margarida, et al. “The Hallucinogenic World of Tryptamines: An Updated Review.” Archives of Toxicology, vol. 89, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1151–73. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-015-1513-x.[↩]

- Chen, Long, and Guang-zhao Huang. “Poisoning by Toxic Animals in China—18 Autopsy Case Studies and a Comprehensive Literature Review.” Forensic Science International, vol. 232, no. 1–3, 2013, pp. e12–23. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.08.013.[↩]

- “Salmonella Infection – Symptoms and Causes.” Mayo Clinic, 29 Apr. 2022, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/salmonella/symptoms-causes/syc-20355329.[↩]

- Ribas, A., and S. Poonlaphdecha. “Wild-Caught and Farm-Reared Amphibians Are Important Reservoirs ofSalmonella, A Study in North-East Thailand.” Zoonoses and Public Health, vol. 64, no. 2, 2016, pp. 106–10. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12286.[↩]

- Tarvin, Rebecca D., et al. “Interacting Amino Acid Replacements Allow Poison Frogs to Evolve Epibatidine Resistance.” Science, vol. 357, no. 6357, 2017, pp. 1261–66. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan5061.[↩]

- Myers, Charles. “A Dangerously Toxic New Frog (Phyllobates) used by Emberá Indians of Western Colombia, with Discussion of Blowgun Fabrication and Dart Poisoning. Bulletin of the AMNH ; v. 161, Article 2.” American Museum of Natural History, 6 Oct. 2005, digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/1286.[↩]

- Gowda, R. M. “Toad Venom Poisoning: Resemblance to Digoxin Toxicity and Therapeutic Implications.” Heart, vol. 89, no. 4, 2003, pp. 14e–14. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.89.4.e14.[↩]