The Sleep Behavior of Frogs

Do frogs sleep? If so… How? Where? And for how long? These are great questions and as of now, scientific research is minimal; a clear answer hasn’t been revealed.

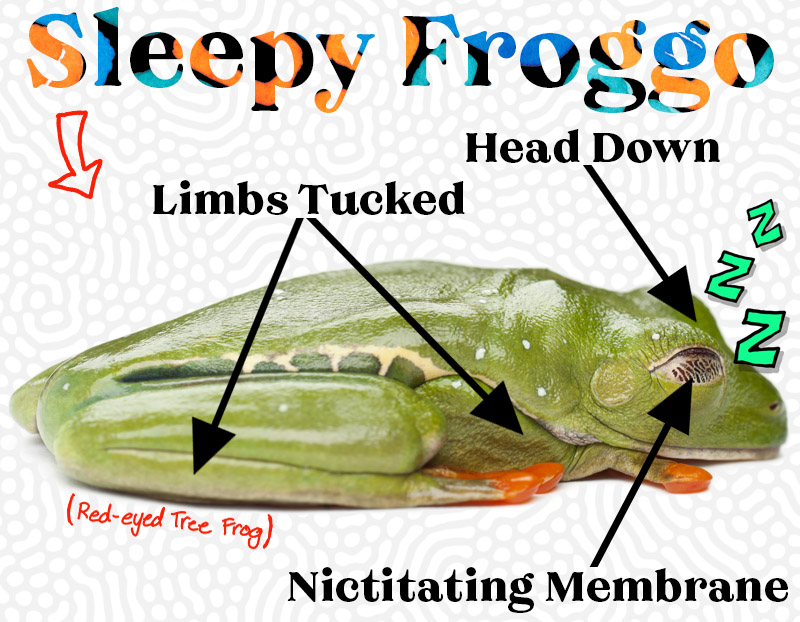

Frogs sleep in different postures, locations, and times. Some species tuck their limbs under their bodies and cover their eyes with a membrane (similar to an eyelid). Terrestrial species, like toads, burrow into the substrate. This happens at all times of the day but frogs are most active at night[1].

Table of Contents

Do Frogs Sleep?

Frogs enter into one of three sleep-like states of rest. It is different from how humans and other mammals sleep. The American Sleep Association [2] explains that humans go through 5 stages of sleep. Our brain waves change, REM (rapid eye movement) occurs, breathing and body temperature change, and a list of other fascinating things occur.

Frogs don’t do this. Their definition of sleep is different from warm-blooded mammals. The next section will glaze over about a century’s worth of research. Don’t worry, it’s a not whole lot.

Research on the Sleep Behavior of Frogs

Henri Piéron, a French psychologist, concluded that all mammals, birds, and reptiles sleep. He arrived at this conclusion through observations in his laboratory back in 1913 [3]. Piéron developed criteria for defining the behavioral state of sleep. Insects, fish, and amphibians met the postural criteria but not the threshold. In layman’s terms: frogs appear to be sleeping due to their posture but they didn’t meet his full criteria for sleep.

Fast forward many years and we have the introduction of an “electrographic criterion of sleep”. A man by the name of J. Allan Hobson studied an American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and found that it did not meet this criterion of sleep [4] either. This further strengthened Mr. Piéron’s conclusion. But why didn’t it meet the criteria?

Even while the bullfrog was “sleeping”, it was able to react to things like food or predators. The bullfrog appears to be resting or sleeping, but it knows if a predator is near; it can hop away. It knows if prey (food) walks by; it can still eat.

Our understanding continues to develop with the research of Karmanova in 1982…

The 3 Sleep-Like States (SLS) of Amphibians

In 1982, Ida Gavrilovna Karmanova was researching the evolution of sleep in vertebrates (animals having a spinal column). Karmanova established that amphibians and fish enter into three sleep-like states (SLS)[5]. The states are listed below.

- Cataleptic Sleep – Protosleep 1 (P1)

- Catatonic Sleep – Protosleep 2 (P2)

- Cataplectic Sleep – Protosleep 3 (P3)

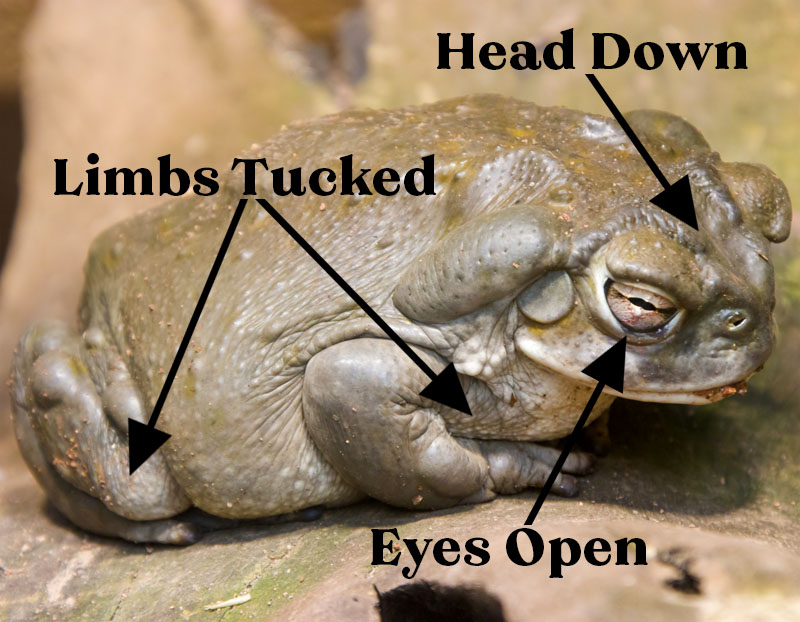

Cataleptic (plastic muscle tone) sleep appears in amphibians during the daytime hours. Their eyes remain open while in this sleep-like state. Catatonic (may have rigid muscle tone) sleep and Cataplectic (may have Atonia) sleep occur during the nighttime hours[6].

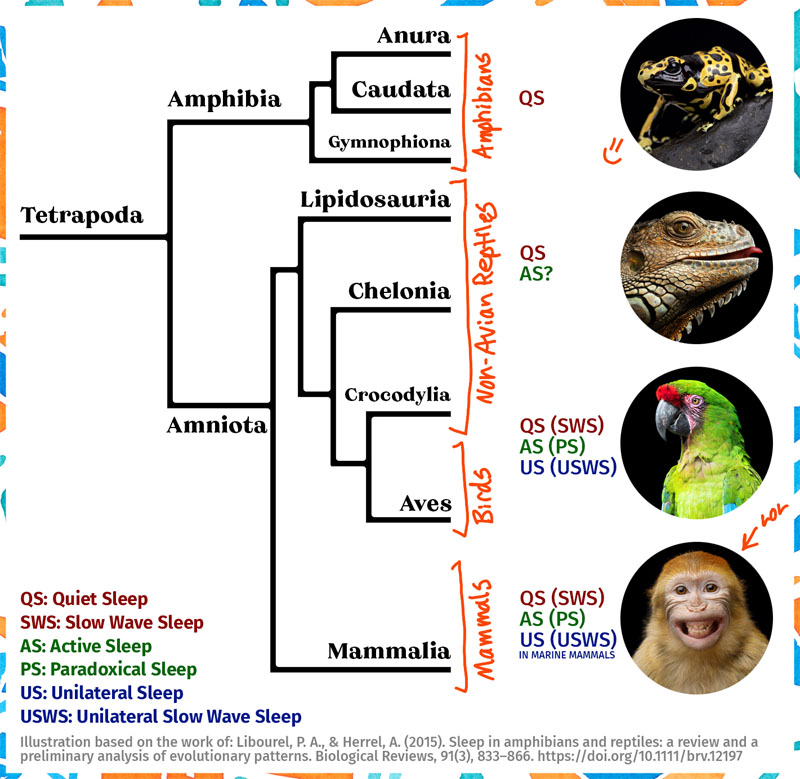

Studying different animals is important for understanding the evolution of sleep. Knowing how amphibians sleep allows researchers to understand how sleep evolved from one species to the next. Understanding changes from amphibians to reptiles, from reptiles to birds, and from birds to mammals, and so on, is essential to painting a clear picture of how sleep evolved along the way.

Class Amphibia and Quiet Sleep (QS)

Another finding comes in the form of Active Sleep, Quiet Sleep, and Unihemispheric Sleep. These states are based on behavioral criteria. Because amphibians are thought to exhibit Quiet Sleep, I’ll briefly cover it here.

Quiet Sleep is a slow-wave sleep-like state. It’s believed to exist in mammals and birds. Mammals also have a state called Active Sleep (REM occurs). Active Sleep has not been demonstrated in amphibians or reptiles and as such, it may have evolved independently.

So, Quiet Sleep (QS) is a non-REM state of sleep while Active Sleep (AS) is REM sleep. These two types of sleep are found in humans, birds, and other mammals. It’s thought that Quiet Sleep applies to frogs [7] but that might not be the case.

Sleep has evolved and applying the warm-blooded criteria of sleep to class amphibia might not be the best way to approach it.

Scientific Research of Sleep in Amphibians is Minimal

This entire section skimmed over the research starting with Piéron in 1913 and ending with Libourel in 2015. For the sake of time and simplicity, I’ve left out information. You can learn more by following the reference links at the bottom of the page. Regardless of this, there are only a few studies concerning sleep research for frogs.

According to Libourel, only 9 Anurans have been studied for their sleep behaviors. Anuran, by the way, is the scientific classification containing all frogs and toads. Moreover, only one species of Caudata (salamanders) has been studied.

To help put this into context, there are over 7,000 species of amphibians in the world. Because of the lack of information, it’s difficult to define exactly what sleep is for a frog.

More About Sleepy Froggos…

Now that we’ve explored the research, I’ll combine the research with personal experience and do my best to explain the common behaviors of a frog’s state of rest. This section will be explained as simply as possible.

Frog Sleeping Postures

Anurans (frogs and toads) have different postures depending on the species and the state of rest they’re in. In my opinion, it’s easier to tell when arboreal frogs are sleeping.

The reason is that they tuck their legs under their body and flatten themselves against the surface they’re laying on. Some species have a neat-looking nictitating membrane (link opens a new tab to Wikipedia) that covers their eyes. This is a clear giveaway.

Here are some indications that a frog is sleeping:

- Limbs are tucked under their body

- Head is pointed downward

- Eyes may or may not be covered by a nictitating membrane

For some species, it can be difficult to tell when they’re resting. In fact, most frogs either sleep with their eyes open (described as “Cataleptic Sleep”) or have a clear or camouflaged membrane covering their eyes.

When Do Frogs Sleep?

Frogs sleep at all times of the day. We learned in the research section that frogs and toads have three sleep-like states. PS 1 happens during the daytime while PS 2 and 3 happen at night.

During protosleep 1, which occurs during the day, their eyes are open and they remain motionless.

Keep in mind, however, that most frogs are active at night. For those of you who keep treefrogs as pets, you’ll know this to be true. There are two sleep-like states that occur throughout the night.

I had two Red-Eyed Tree Frogs several years ago and they would seemingly vanish during the day. They tuck their limbs, covering their colorful markings, and hunker down on leaves, out of sight. They livened up and became more active at night.

Burrowing species, mostly toads, spend a lot of their time in the soil during the daytime. I imagine they’re in Protosleep 1 while burrowed into the soil. Their eyes can remain open in case prey walks by, at which point they will catch it and eat. After all, toads are ambush predators.

How Long Do Frogs Sleep?

The research I came across didn’t attempt to determine how long frogs are in a state of sleep. Even if it had, the findings would be subjective to the species examined.

To answer this question I’ll give you some examples of personal observations. My sons’ have a Pacman Frog and he spends most of his time burrowed up to his eyes in the substrate. It’s hard to tell whether or not he is in a sleep state. If I had to guess, I would say he is.

Also, the Red-Eyed Tree Frogs I kept would spend the entire day in a sleep-like posture, only becoming active at night. I checked on them often at night but never stayed awake to see if they were resting.

My estimation is that most frogs, including the two I just mentioned, spend 10+ hours in a state of sleep each day. The Red-Eyed Tree Frogs I kept held a sleeping/resting posture for 12 – 14 hours per day (during the daytime) and that doesn’t include the time they slept at night.

Where Do Frogs Sleep?

The answer to this question depends on the type of frog.

- Arboreal species spend their time in trees. You’re likely to find them on the underside of leaves, inside hollowed trees, in flowers, and away from direct sunlight.

- Aquatic species are found in the water. There are semi-aquatic and fully-aquatic species. You can find them between rocks, in and around plants, and in anything type of under water shelter.

- Terrestrial species are those that can’t climb well. They spend their time on the ground. Burrowing species can be found in the substrate while non-burrowing types will take shelter from the sun. You can find them in leaf litter, in logs, between rocks, and in cool, damp areas.

TLDR; Do Frogs Sleep?

Frogs enter into a sleep-like state of rest. It’s different from humans and mammals. Some research suggests there are 3 types of sleep-states amphibians can be in. The names of them are cataleptic, catatonic, and cataplectic; they occur at different times of the day.

While a frog is “sleeping”, it maintains awareness of its surroundings. Their eyes are open in one of their sleep states (cataleptic). It can be difficult to determine whether or not a frog is sleeping. Sometimes you can tell by their posture. They tuck their legs under their body, sometimes tilt their head down, and some species have a web-looking membrane that covers their eyes.

There are very few studies regarding the sleeping behavior of frogs. In fact, only 9 species of frogs out of the 7,000 + species of amphibians have been used in this research as of 2015.

Long story made short: We need more research on this topic. We know frogs have a state of rest or sleep, but it’s quite different from the way mammals sleep. Mammals have Quiet Sleep (QW) and Active Sleep (AS). It’s believed that amphibians have Quiet Sleep only, a non-REM state of sleep.

Featured photo of Red-Eyed Tree Frog by: Eric Isselée / Adobe Stock

References

- Thomas, Oliver. “Sleeping Site Fidelity in Three Neotropical Species of Herpetofauna.” Spring 2021, no. 155, Spring 2021, 2021, pp. 8–11. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.33256/hb155.811.[↩]

- ASA Authors & ReviewersSleep Physician at American Sleep Association Reviewers and WritersBoard-certified sleep M.D. physicians, scientists, editors and writers for ASA. (2021, July 27). What is Sleep & Why is It Important for Health? American Sleep Association. https://www.sleepassociation.org/about-sleep/what-is-sleep/[↩]

- Hobson, J. Allan, et al. “Sleep Behavior of Frogs.” Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences, vol. 30, no. 3, Temporary Publisher, 1967, pp. 184–86, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24314832.[↩]

- Allan Hobson, J. (1967). Electrographic correlates of behavior in the frog with special reference to sleep. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 22(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(67)90150-2[↩]

- Aristakesian, E A. Zhurnal evoliutsionnoi biokhimii i fiziologii vol. 47,4 (2011): 296-305.[↩]

- Libourel, P. A., & Herrel, A. (2015). Sleep in amphibians and reptiles: a review and a preliminary analysis of evolutionary patterns. Biological Reviews, 91(3), 833–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12197[↩]

- Lesku, John A., et al. “Evolution of Sleep and Adaptive Sleeplessness.” Handbook of Sleep Research, 2019, pp. 299–316. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-813743-7.00020-7.[↩]