Frog Skeleton: An Overview (with Diagrams)

The skeleton of a frog includes many parts; around 140 bones (depending on the species). Frogs are tetrapod vertebrates (having four legs and a backbone) with the unique ability to leap many times the length of their body.

On this page, we will take a closer look at a frog skeleton and explore the different parts with the help of diagrams and pictures.

Table of Contents

Frog Skeleton

Refer to the interactive diagram above to learn where each part is located.

- Maxilla – Forms the upper jawbone

- Atlast – The top part of a backbone

- Suprascapula – Shoulder blade

- Vertebrae – Individual bones that form the spine

- Sacral Vertebra – A bone below the last vertebra, positioned between the hips

- Urostyle – A long, thin bone at the base of the lower vertebrates

- Ilium – A flat bone stretching backward from the Sacral Vertebra

- Femur – Upper bone of the rear limb

- Tibiofibula – A single bone commonly known as the shinbone

- Tarsus – Several bones formed between the Tibiofibula and Metatarsus

- Metatarsus – Bones forming the foot of a limb

- Phalanges – Several bones forming fingers or toes of a limb

- Humerus – Upper bone of the front limb

- Radio-ulna – A forelimb bone

For a more detailed diagram, check out this PDF on the study of esteology of frog by IGNOU.

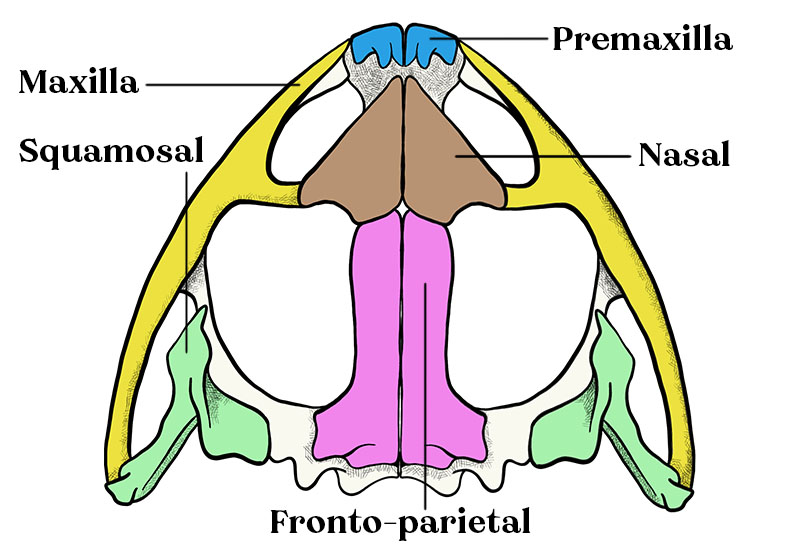

A Frog’s Skull

A frog’s skull consists of three main regions: Cranium, Sense Capsules, and Jaws. Moreover, a frog’s skull is generally known for having a triangular shape and incomplete ossification.

Ossification refers to bone formation – the process of soft tissues becoming hardened.

- Cranium – The front of a frog’s cranium is more developed than the back. It serves to protect the brain.

- Sense Capsules – Cartilaginous cavities which contain the sensory organs: eyes, nose, etc.

- Jaws – The upper and lower jaws support the border of the mouth.

Shapes and Differences in Frog Skulls

Accord to researchers [1], Anurans (frogs and toads) have evolved hyperossification at least 25 times.

Hyperossification is the formation of more bone material than what is typical.

A good example of this is seen in the Amazon Horned Frog. They have a rather large skull in proportion to their body (see the picture above).

The large skull, accompanied by a wide jaw, gives them the ability to eat larger prey. Having that ability helps ensure their survival. Adult Amazon Horned Frogs, commonly known as “Pacman Frogs”, are capable of swallowing small animals like lizards, other frogs, snakes, and even birds.

Bruno’s casque-headed frog (Aparasphenodon brunoi) and Greening’s Frog (Corythomantis greeningi) are two prime examples of hyperossification of a frog’s skull. The head appears smooth from the outside but underneath the skin, both frogs have tiny spines on their skull – primarily around their nostrils.

In this case, the abnormal amount of bone serves as a defense mechanism. Bruno’s frog secrets a toxin more powerful than that of a pit vipor [2]. If an animal were to bite down on the skull of this frog, the spines could pierce the predator; effectively injecting them with the powerful toxins in their skin.

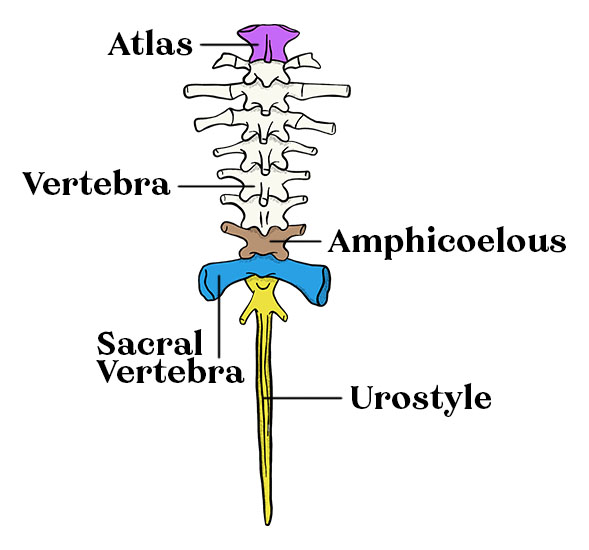

A Frog’s Vertebral Column (Backbone)

The vertebral column of frogs contains up to 10 vertebrae [3]. This includes the Atlas, which is the first vertebrae, and the Sacral Vertebra which is the last.

As far as similarities go, the first, eighth, and ninth vertebra have a different shape than the others. In between the first, eighth, and ninth vertebra are the “typical vertebra” which are aptly named due to their similarities in structure.

Seen directly after the ninth vertebra is the Urostyle. The urostyle is a long, thin bone extended off the bases of the vertebral column.

Frogs don’t have “true joints” between the vertebrae. Their embryonic development produces vertebrae that appear to be hollowed out on the front and at the back or on one side only. The entire backbone serves to protect the spinal cord.

Absence of Neck, Tail, and Ribs

The neck is a skeletal structure found in most vertebrates but not in frogs. Frogs and toads cannot turn their heads because they lack a neck. They are also unable to raise or lower their heads.

Actually, a frog’s body is perfectly designed for jumping[4]. A neck would make the frog vulnerable while jumping, just as a tail would get in the way when jumping (which is why frogs have lost their tails and developed a urostyle).

A wrong turn of the head could result in a broken neck and death. Frogs move more safely because of their shorter, rigid spine and lack of a neck.

One more unique feature is that they don’t have ribs. The frog’s inhalation process is different from humans. The role of ribs and diaphragm in humans helps to decrease pressure in the lungs, allowing outside air to flow in by expanding the chest cavity.

Frogs breathe through dilation and contraction of the buccopharyngeal cavity. In the dilation process, the frog’s mouth is closed while air is inhaled through the nostrils. Then, keeping the nostrils closed and the glottis open, air passes from the buccopharyngeal cavity to the lungs. For exhalation, the glottis and nostrils both open while air is exhaled from the lungs

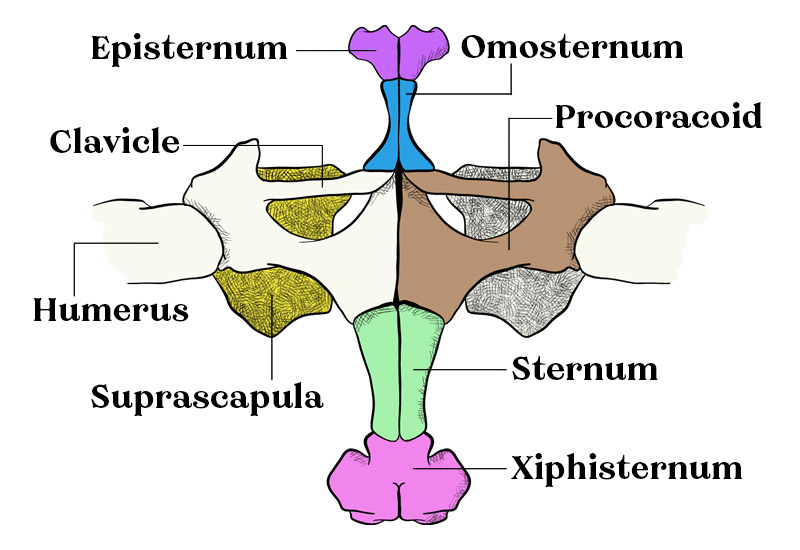

A Frog’s Girdles

Frogs have two girdles; the pectoral girdle and pelvic girdle. A girdle is a structure of bones that connects limbs to the main axis of the body.

In the case of amphibians, the pectoral or shoulder girdle is a series of bones that connects the front limbs to the axis of the body.

Pectoral Girdle

The illustration above is the ventral (underneath) view of a frog’s pectoral girdle. To get a better visual, look at the Suprascapula. The Suprascapula is the shoulder, as seen from the underside of the frog’s skeleton.

- Episternum is the upper part of the sternum.

- Omosternum is in between the episternum and clavicle on a frog.

- Clavicle is essentially a frog’s collarbone. It is in between the shoulder and sternum.

- Humerus is the first bone in the front leg of a frog. It runs between the shoulder and elbow.

- Procoracoid is the amphibian equivalent of a coracoid [5].

- Sternum is connected between each half of the pectoral girdle, between the Xiphisternum and Propcoracoid.

- Xiphisternum is the lowest piece of the sternum.

The parts listed in this diagram are by no means everything!

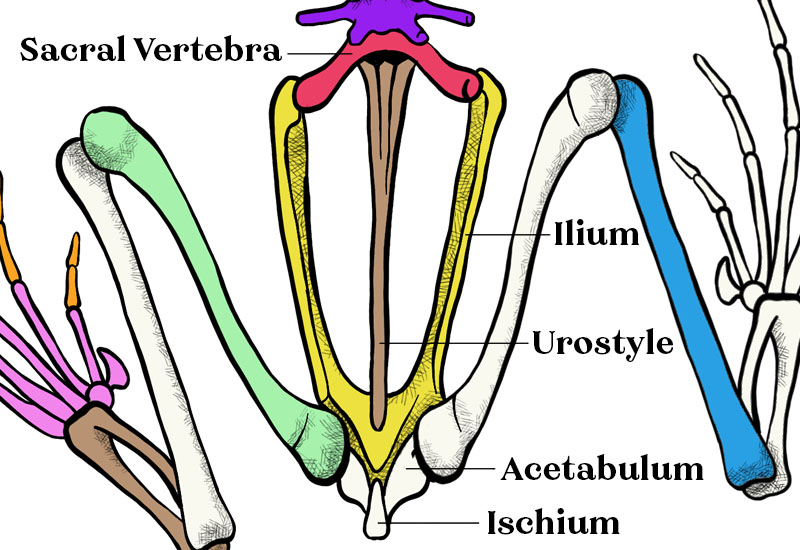

Pelvic Girdle

The illustration above is the dorsal (top) view of a frog’s skeleton. More specifically, it’s the pelvic girdle of a frog. As for our picture, only five parts are labeled and as such, it’s not the most in-depth diagram but it works as a basic overview.

- Ilium – A bone forming the upper part of the pelvis

- Urostyle – Formed from fused vertebrae at the base of the backbone

- Acetabulum – A socket of a frog’s hip, in which the femur bone fits

- Ischium – A curved bone at the base of the pelvis

A Frog’s Limbs

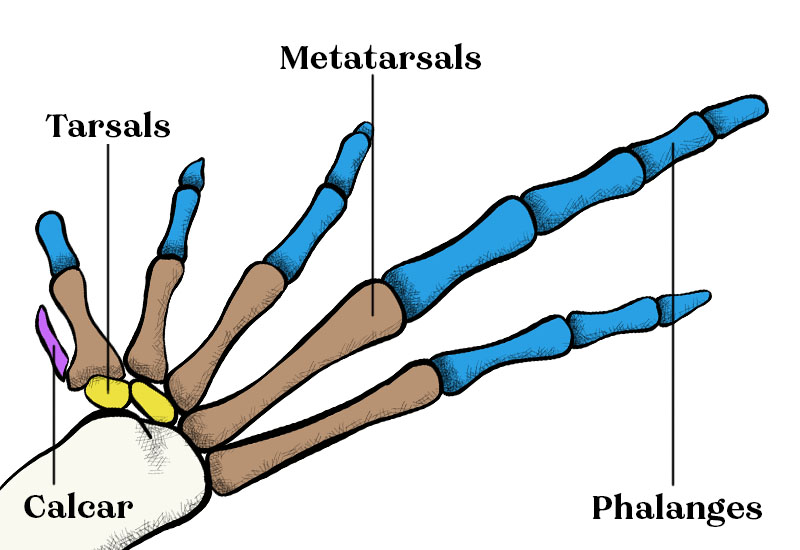

The hind limbs of a frog consist of the femur, tibiofibula, tarsus, and feet. The femur, Tibiofibula, and tarsus are labeled in the diagram at the top of the page.

Upon closer inspection of the foot, you’ll find the tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges.

- (most) Anuran have a phalangeal formula of 2-2-3-4-3 on their toes.

- (most) Anuran have a phalangeal formula of 1-2-3-2 on their fingers.

It’s not uncommon to see frogs or toads with a phalangeal formula of 2-2-3-3 on their fingers. Keep in mind, not all are the same.

Most frogs have five digitals on their feet (toes) and four digits on their hands (fingers). To make a simple comparison, phalanges are like fingers (or toes) while the tarsals and metatarsals form the foot. You can see both labeled in the diagram above. As for the hands, which I didn’t provide a diagram for (sorry), the carpal bone and metacarpus form the hand while the phalanges are the fingers.

Ossification: Cartilage & Bone

As you already know, frogs begin their life in a larval form, as tadpoles. The first stage begins with the eggs being laid and fertilized, which typically happens outside of the female’s body. A clutch or string of eggs is gently laid in pools of water, streams, ponds, etc.

Tadpoles grow within the eggs and eventually hatch into water. At this point, they don’t have bones. They’re comprised of cartilaginous tissue. As you can see by the pictures of the adult frogs below, that obviously changes.

Ossification is the natural process of bone formation. During metamorphosis and the early parts of a froglet’s life, some of its cartilaginous tissue forms into bones.

Fun Resources to Learn More About Frog Skeletons

This page covered the basic parts of a frog’s skeleton. It was meant to be easily digestible for hobbyists that want to learn more about the skeletal system but not necessarily study the topic.

If you, on the other hand, would like to study this topic in more detail, well, I’ll point you in the right direction! In the table below, there are two academic sources about frog skeletons. In addition to this, there is also a link to an iOS and Android app with a 3D frog skeleton!

| Format | Topic and Link |

|---|---|

| Web | Study of the Endoskeleton of Indian Frog |

| Study of Osteology of Frog: Disarticulated Skeleton | |

| iOS | 3D Frog Skeleton App |

| Android | 3D Frog Skeleton App |

I truly hope this piece of content was helpful to you! I hope you learned something. If you found this interesting, I bet you would find a 4D frog anatomy model enjoyable as well!

Finally, if you find frogs or amphibians interesting, take a look around the website. I’m constantly adding informational posts like this, usually with custom illustrations, diagrams, and pictures. You’ll find care guides for keeping amphibians as pets, too!

References

- Paluh, Daniel J., et al. “Evolution of Hyperossification Expands Skull Diversity in Frogs.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 15, 2020, pp. 8554–62. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2000872117[↩]

- Jared, Carlos, et al. “Venomous Frogs Use Heads as Weapons.” Current Biology, vol. 25, no. 16, 2015, pp. 2166–70. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.061[↩]

- Hofrichter, Robert. “The Encyclopedia of Amphibians.” The Encyclopedia of Amphibians, Gardners Books, 2000, p. 66.[↩]

- Jorgensen, M. E., and S. M. Reilly. “Phylogenetic Patterns of Skeletal Morphometrics and Pelvic Traits in Relation to Locomotor Mode in Frogs.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology, vol. 26, no. 5, 2013, pp. 929–43. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12128.[↩]

- Vickaryous, Matthew K., and Brian K. Hall. “Homology of the Reptilian Coracoid and a Reappraisal of the Evolution and Development of the Amniote Pectoral Apparatus.” Journal of Anatomy, vol. 208, no. 3, 2006, pp. 263–85. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00542.x[↩]